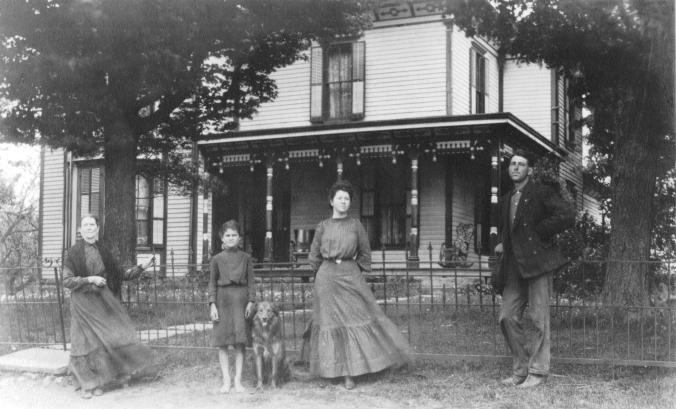

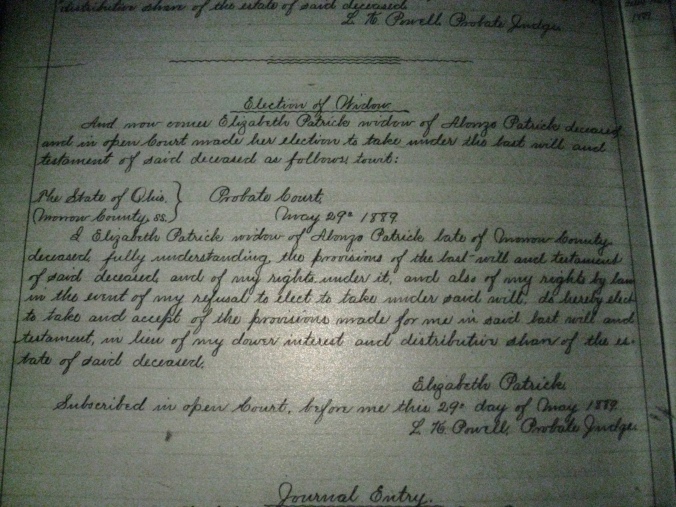

Jerry flew two back-to-back missions to the French city of St. Lô in late July 1944. The first of these sorties– his fifth overall — took place on July 24, 1944.* This date marked the end of the Normandy invasion and the beginning of “Operation COBRA,” the next phase of the Allies’ push into France. The 12th Army Situation Map above shows the positions of Allied and Axis forces on this date.

By the time Jerry flew his missions to St. Lô, the city had be the scene of intense ground fighting and had been bombed by both Allied and Axis troops. St. Lô was so devastated by the war that then-journalist and later playwright Samuel Beckett famously dubbed it the “city of ruins.” The picture below shows why this name was so fitting.

![Normandie Front [1944] St. Lô. Ein schwerbeschädigtes Stadtviertel.](https://farmscreeksandhollows.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/bundesarchiv_bild_146-1984-043-03_frankreich_st-_lc3b4_zerstc3b6rungen.jpg?w=676&h=501)

Normandie Front [1944] St. Lô. Ein schwerbeschädigtes Stadtviertel. German Federal Archive (Deutsches Bundesarchiv)

According to the 8th Air Force Historical Society’s Chronology, Jerry’s B-17 and other “heavy bombers [were] scheduled to participate in a US First Army offensive (Operation COBRA) to penetrate the German defenses [west] of Saint-Lo [sic] and secure Coutances” on July 24, 1944. The 457th Bomb Group’s narrative account of the mission provides the following background:

“The United States First Army, after overrunning the Cotentin Peninsula and storming Cherbourg, had regrouped on the north side of the straight road running from St. Lo to Lesay. It was now poised for a break-out into the French countryside to the south, and the Brest Peninsula. Fifteen hundred eighty-six heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force were called upon to assist in the grand drive…”

The Chronology reported “1,586 bombers and 671 fighters [were] dispatched” for the mission. They flew “a direct route to the front lines” but “the cloud cover below was almost complete,” according to the 457th Bomb Group Narrative, which continued:

“The coast was crossed with the target area sixteen miles away and still the clouds persisted. As no landmarks were visible the course could not be checked and corrected. Finally the formations came out into the clear about a mile north of the road, thirty seconds time for bombs away. All boxes were about a half mile to the right of their aiming points, but could not turn left because of crowding and the abreast formation. As American troops were 1500 yards away from the road, the bombardiers in the lead ships waited to release until they were sure bombs would not fall short. All bombs were away except those in the low box. The other three boxes reformed and made a 360 over the channel waiting for the low box to go back over the target area. On this second run, the clouds had moved over the German positions and no release was made. At this moment the entire operation was cancelled. Only 487 of the 1586 bombers had dropped their bombs.”

They would return the following day.

Text Sources:

* Jerry’s Sortie Record.

** The 8th Air Force Historical Society’s Chronology, available online at http://www.8thafhs.org/combat1944b.htm.

*** The 457th Bomb Group Mission Narrative, available online at http://www.457thbombgroup.org/Narratives/MA94.HTML

Photo Sources:

The map at the top of this post is” [July 24, 1944], HQ Twelfth Army Group situation map.” Allied Forces. Army Group, 12th. Engineer Section. Accessed through the Library of Congress Geography and Map Division Washington, D.C. 20540-4650. Library of Congress Catalog Number2004629087. http://lccn.loc.gov/2004629087

The second image above is “Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1984-043-03, Frankreich, St. Lô, Zerstörungen” by Unknown – This image was provided to Wikimedia Commons by the German Federal Archive (Deutsches Bundesarchiv) as part of a cooperation project. The German Federal Archive guarantees an authentic representation only using the originals (negative and/or positive), resp. the digitalization of the originals as provided by the Digital Image Archive.. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0-de via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1984-043-03,_Frankreich,_St._L%C3%B4,_Zerst%C3%B6rungen.jpg#mediaviewer/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1984-043-03,_Frankreich,_St._L%C3%B4,_Zerst%C3%B6rungen.jpg.